In Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire, the heroine takes rides on a streetcar line named Desire to come to the city centre. In New Orleans, there really was a line by that name. If a tramway in a city in the US could be named Desire, then the taxi route to the hill town of Darjeeling could very well be named Longing. To understand this, one would have to visit Chowk Bazaar on a dim, foggy afternoon. There one would see the battered Mahindra, Willys and Land Rover service jeeps waiting in front of the police outpost, below Golghar restaurant, and hear the impatient cries of drivers and their assistants:

‘Silgarhi-Silgarhi-Silgarhi

Kharsang-Kharsang-Kharsang

Last turn! Last turn!’

Last turn. After this no taxi would ply on the hill roads. And Darjeeling would be completely cut off at night from the rest of the world. During my years of exile there, every time I would hear the anxious calls of these men, I would feel a sudden tug at my heart. Their litanies would blend with the muezzin’s call for evening prayer rising from Butcher Bustee below and fill me with a deep longing.

One of my colleagues had an eight-year-old son who suffered from asthmatic fits. These came unannounced, and the boy had to be rushed to a lower altitude as there was no other remedy. The jeep drivers’ calls would cast a shadow upon the distressed father’s face. Another colleague, who had an odd sense of humour, would respond by singing aloud a Tagore song:

‘Orey ay, amay niye jabi ke re bela sesher sesh kheyay

Orey ay, diner seshe…’

‘Oh come! Who’ll carry me in the last ferry at day’s end…

For whom the daylight has died but the lamp of the night

has not been lit, it is he who is sitting at the pier.’

The light of the day would really die for us with the ardent cries of the last-turn drivers, the lamp of the night would not be lit, and we would plod our way to the pier… In our case, to one of the many pubs in town.

I have heard the anxious footsteps of the villagers who had come to town on work, and were hurrying to catch the last-turn service jeeps. With nightfall, not only would Darjeeling be cut off from the plains, but the settlements scattered all over the hills, too, would shrink into tiny islands in a dark ocean, the mountains would return to primaeval times. The darkness would thicken over the jeep stand, the calls would grow mystical and indistinct:

‘Kalempoong-Kalempoong-Kalempoong!

Lebong-Lebong-Lebong!

Kharsang-Kharsang-Kharsang!

Last turn! Last turn!’

A perceptive ear could pick out in these slurred utterances the roots of the original Lepcha place names that the jeep-drivers unconsciously evoked. Thus, Kurseong became Kharsang, Lebong became Alebong, and Darjeeling became Dorhzeling. In the Lepcha language, each of these words has a meaning: Kharsang means the land of white orchids (alternately, the star at dawn), Alebong is a tongue-shaped spur, and Kalempoong is ‘the ridge where we play’. In fact, many peaks, rivers, gorges and plateaus in these hills still bear Lepcha names whose sounds have been twisted in other tongues. Thus, Peshok comes from pazok, which means forest; Mirik from mir-yok, ‘a place burnt by fire’; Phalut from Fak-lut, ‘the denuded peak’; and Senchal comes from shin-shel-lo, meaning cloud-capped hill.

That the Lepchas were the original inhabitants of the Darjeeling hills comes through loud and clear with these words. Official British documents also acknowledge this. But that shouldn’t stop us from taking a critical look at the picture of a wild forested hill tract, twenty-four miles long and six miles wide, dotted here and there with a few Lepcha dwellings, that the East India Company received from the Rajah of Sikkim as a gift. Fact is, this has been one of the oldest inhabited stretches in the Himalaya and many migrating tribes and communities, herders and pastoralists, were crisscrossing it for centuries. On the part of the Company, the object of seeing, and showing, Darjeeling hills as virgin territory was two-fold: one economic, the other, cultural. For the tenancy of this hill tract, the Company had agreed to pay the Rajah an annual grant of three thousand rupees (the amount was later doubled). Lack of human habitation and, consequently, limited scope for revenue-collection would have meant that the gift was rather profitable for the Rajah. And then there was the colonial mindset at work behind the notion that Darjeeling was ‘discovered’ by the British. This led to the fabrication of a nostalgic home town on foreign soil, upon exotic Himalayan terrain.

This fabrication progressed through the nineteenth century on a war footing; a military officer, Lt. General (then Captain) George Aylmer Lloyd was even appointed for it. In 1835, after the Company obtained the Darjeeling hills as a gift, it sent Lt. General Lloyd and Dr A. Chapman, the surgeon of the Governor General, to sojourn there and to find out whether its environment and climate were suitable for a sanatorium. They stayed there for eight months in a wattle hut that they built for themselves. Based on their report, the Darjeeling Association was formed in Calcutta with a brief to set up a town in the mountains. The years 1838-39 were a period of intense activity in Darjeeling. Jungles were cleared and plots of flattened land were distributed among members of the association. Also, and crucially important, the construction of a bridle path from the plains to Darjeeling via Punkhabari began. The Darjeeling Family Hotel was set up; a colony came up with about a dozen cottages. St. Andrew’s Church was built in 1843; Loreto Convent was established four years later. In the lower part of the settlement, not yet a town, dwellings for coolies and menials were coming up now as a large native labour force was sine qua non for the comforts of the sahibs and memsahibs. This led to the growth of temples and a mosque in 1851-52. The monastery in Ghoom was built in 1876, and another in Bhutia Bustee came up three years later. In 1880, the educated Bengali babus who had been flocking to the hill station as clerks and teachers established a temple of the Brahmo faith.

Thus the tradition of people practising their different faiths in Darjeeling is as old as the town itself. But what is remarkable is that as many as nine churches and chapels were built here before the end of the nineteenth century. This was the Victorian age; British social life was drawn tight by the contrary pulls of orthodoxy and libertinism, even thousands of miles away from home. Since the Suez Canal was opened in 1869, more and more memsahibs

had begun to arrive in India, but the officers posted in the mofussils did not have much opportunity to mix with them. The carefree life in the hill stations and the merry grass widows who reigned there compensated for this. Their scandalous lives at Shimla have left their marks in the writings of Kipling; that of their Darjeeling counterparts are scattered in letters, diaries and juicy anecdotes the hill people have inherited from their forefathers. There is, for example, the apocryphal story that the manager of Wilson’s Hotel would ritually walk the corridors at daybreak ringing a bell so that the lodgers could return to their respective rooms before morning tea was served.

1857 was a watershed year in the history of Indian hill stations. The mutiny made it starkly clear that these mountain retreats were of crucial importance to the colonizer, not only from the point of view of health and recreation, but also of security. A few thousand feet above the heat-scorched plains, they felt safe and out of harm’s way. Apart from the topography, this also had something to do with the native population. By this time, the stereotype of hill people—and they included the Lepchas of Darjeeling, the Paharis of Shimla and the Todas of Ootacamund—as the epitome of simplicity and reliability had been set.

All who saw them would prefer their open and expressive countenances to the look of cunning, suspicion or apathy that marks the more regular features of the Hindoostanee. …They are the most good-humoured, active, curious yet simple people, that [I have] ever met with.

This is one Captain Herbert, who visited Darjeeling in the 1830s to inspect its suitability as a sanitarium. John C. Lowrie, an American Presbyterian missionary, seems to echo him:

In the manner of the Hill people there is a frank and independent bearing, which is much more pleasant than the sycophancy and servility towards superiors so common in India. They seem to be very ingenuous. They might be characterized as a simple-minded people.

Coincidentally, in the year 1857, when the seeds of mistrust and iron rule were being sown in the plains of India, saplings of tea were being planted for the first time in Makaibari. In 1864, the residential St. Paul’s School was set up. The following year, Darjeeling got its first official cemetery and a prison; the town’s population was three thousand in 1872. Eight years later, the marvel of engineering chug-chugged up the hill blowing whistles and waving banners of smoke. The dense primaeval forest cover was magically transformed into the green undulating velvets of tea gardens.

Such a whirlwind tour of history has its pitfalls: the timeline drawn to connect the points of apparently significant events eludes other events, or non-events; the eye fails to discern the gaps and ruptures in the imagined line. Our tendency to draw the line straight through clusters of happenings tends to skirt the winding tracks and dead alleys of history.

But no path in Darjeeling is straight. To know it intimately, one must step out of the broad roads and take the twisting hill tracks and steep side trails. Local people call them chor bato.

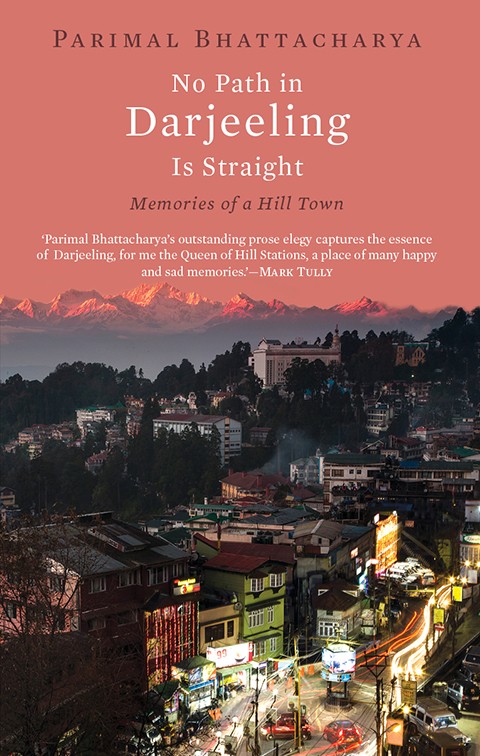

Excerpted with permission from No Path in Darjeeling Is Straight, Speaking Tiger.

Pages: 200 Price: Rs 450