Parthajit Baruah, author of Face to Face: the cinema of Adoor Gopalakrishnan, decodes Elippathayam (The Rat Trap), the director’s third feature film that released in 1981

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Elippathayam, the third feature film released in 1981, is unquestionably one of the finest poetical works of art in the history of Indian cinema. The film Elippathayam unfolds a human relationship that remains a perennial issue in the wider social context of Kerala. Set in the 1940s, the film draws the picture of the vestige of feudalism as well as the matrilineal structure of the society in Kerala which is narrated with a delicate mixture of metaphorical language and lyricism. Elippathayam is the masterpiece of the auteur that documents the feudal society in Kerala. In fact, it critically analyses the tragic journey of a family that is caught in the whirlpool of the decaying past.

The minute details of the decaying history of feudalism with the opening establishing shots of the house like the viali (the lamp-stand), that is considered to protect the house from evil influences, the oil lamp, the Chinese jar, the heavy ancient door, the iron keys, key holes, the abandoned cot, aesthetic design of the wooden ceiling and a non-functional wall clock that always remains stuck at 6.28, are clear reflections of the old ancestral house which metaphorically suggests of the feudal background of the family. The use of the key-hole image is very significant because it reminds of the Peeping Tom or vouyerism. Adoor himself says on the use of the keyhole, “I have used the keyhole very significantly as if the whole film is a peering through the keyhole.”

The film focuses on Unnikunju, a middle aged man with an extreme form of feudal mentality. He is an ego-centric self-centred, insensitive, weak-willed and inert person who likes to live in his own world escaping from facing the challenges of the outside world. He withdraws like a rat into a closed chamber. He suffers from a sense of narcissism and is often found preening himself, cutting and cleaning his nails, massaging oil on his body and trimming his moustache. He is a symbol of a patriarchal figure in feudal society who is completely dependent upon his sisters. He does not want to go out of his self and share love and thus, stays away from Menakshi, a married woman in the same village who passes him varied sorts of sensuous gestures. The world around Unni is changing, but he refuses to change and cuts himself off from the outside world.

Unnikunju has three sisters – Janamma, his elder sister, who is married, living with her children. Sometimes, she visits him to claim the share of her property. His two unmarried younger sisters are Rajamma and Sridevi. Rajamma, a devoted sister, takes care of Unni day in and day out like an unpaid slave. She irons his shirts, brings his slippers and umbrella while going out to attend marriage ceremonies, boils water for him, cooks for him and almost forgets her ‘self’ or individual. She suppresses her passions, desires and dreams and never lets it get known. When she wants to go out of this trap by marrying a man and find a new world of her own, Unni rejects the marriage proposal citing different reasons. She is very loyal to her brother and never utters a single word against him. The youngest sister of the house is Sridevi, a college student who spends her time living in her own romantic and dream world. Whenever she stays in her room, she is found adorning herself, reading romantic books and jotting down some sort of billet doux.

Adoor symbolically uses certain images to manifest the different and contrasting natures of Rajamma and Sridevi. Rajamma’s inexplicable suppressed feelings are haunted inwardly while Sridevi’s feelings are overtly picturised. In one scene of the film, Adoor shows the roof of their house and the well with a top angle shot. There lie unwashed vessels and utensils at the backyard of their house and here, Adoor uses the sound of the aeroplane flying in the sky as the image of flight. As soon as Sridevi hears the sound of flight, she is excited and enthusiastic. She looks up at the sky and calls her sister Rajamma, “Sister, sister, hurry up, there is a plane! Come quick – it will disappear.” Rajamma comes out and looks at a different direction of the sky and says, “Where is it?” She continues to look at the sky enquiring where it is. She cannot see it. Sridevi says to her, “Too late. The plane cannot wait for you.” Rajamma, due to glaring sunlight, covers her eyes and sits down feeling something different. Sridevi says, “What’s the matter, sister?” Rajamma says with tears in her eyes, “I feel I’m going blind… I feel better. I can see now.”

In Kerala, the sapling of the coconuts is regarded to be very precious because one’s life is attached to it. They are always protected by the head of the family. In a particular scene of this film, Unni is shown on the verandah reclining on the traditional wooden resting-chair reading a newspaper. Suddenly, a cow enters the courtyard and starts devouring the coconut sapling. Unni, instead of shooing away the cow himself, calls Rajamma to do the same. This scene talks of the inertia that is deeply rooted in the mind of Unni because of the feudal background.

The image of the non-functional old wall clock has been used as a recurring motif in the film to imply that time has ceased to move ahead inside the compound of this ancestral house. The dead clock is, in fact, Unni himself who remains static and stagnant in his thoughts and does not like to accept any change. With every moment time runs and with the change of time, one can notice the social changes and transformations. Certain things have been changed in this house but Unni does not change like the clock. He remains where he was in the beginning of the film. Sridevi leaves the cage-like house with her lover in search of free air, an ambiance without suffocation. Unni remains unaffected by it but as soon as Rajamma suffers from serious illness and the villagers carry her away with care, he breaks down. Probably, he rues the loss of his ‘obedient maid.’ Without Rajamma he is in utter dread of facing life and withdraws like a poor rat into a closed chamber. In the huge ancestral house he is pathetically left alone.

At the end of the film, Unni is seen trapped in the closed chamber of his house. People of the village chase, carry and throw him in the cold water of the village pond in the dead of the night. They want him to drown in the cold water but Unni comes out of the water like a rodent with folded hands which as we know, is a typical posture when one gets wet and trembles. One interpretation of the ending is often given that Unni who is always engrossed in himself, gets the punishment which is a sort of poetic justice meted out to him. But Unni, a selfish middle-aged man, is a perfect instance of feudalism and patriarchy who is never moved even by the severe illness of Rajamma and who likes to stick to the past without reflecting his emotions. Unni may be unaffected and unmoved, or may not show his emotion, but he has a thinking mind which is mantled with the layers of his heartless heart.

Water has always been metaphorically used as symbol of purification. Water purifies the dirt and the stains. Thematically speaking, Unni, a symbol of crude feudalism, who always wants to wear the garments of the past feudal history, refuses to take bath because he thinks that it will wash away his feudal glory.

Elippathayam has a poetic sophistication in structure. As the story rolls on, Unni seems to find himself caught like a rat, and in the end of the film, he is drowned in the village pond. He is thrown out of the trap like dying feudalism. Unni’s loyal sister, Rajamma, is carried away for proper treatment from the ancestral house by the kind-hearted village people. Again, the youngest, sister, the first one to leave the trap-like house, elopes with her lover. Finally, their ancestral house is abandoned by the people living there. But the ancestral house will continue to symbolise the decay and dying of the social system. It will stand still, unperturbed. Sridevi, Rajamma and Unni’s departure from the house are equated with three rats that are taken by Sridevi for drowning.

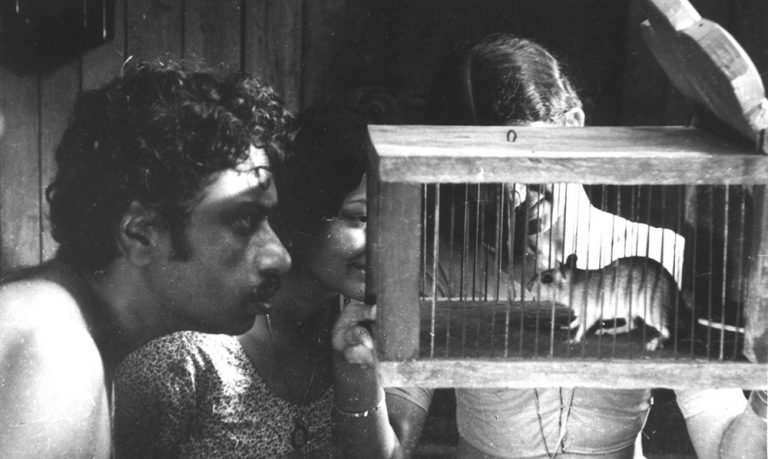

Cover picture from the film Elippathayam courtesy: adoorgopalakrishnan.com

Comments are closed.