The giraffe beamed. She had been grazing on an acacia tree by the side of the road. When Maxine stopped the car to get a good look at her, she reciprocated her curiosity. The giraffe stuck her head in through the window and, well, yes, smiled at her. Maxine suddenly felt like a child and wanted to squeal with excitement and just a smidgen of glorious fear. The ossicones of the giraffe lightly brushed Maxine’s shoulder as the gentle creature slowly straightened out to her full height and went back to eating acacia twigs.

Maxine drove on through the dusty savannah, imagining that she was in an old photograph. The ubiquitous dry tall grass and the smattering of leafless baobab trees that secretly hoarded water in their giant trunks were all in shades of pale sepia. Maxine never stopped marveling at how the seemingly dead sentinels of the East African savannah, the baobabs, revealed their inner life with an overnight growth of greenery – when there was even the lightest shower of rain. Lately, though, there had been no precipitation.

Well before Maxine caught her first glimpse of Mount Umer, she sensed it. A cool shadow seemed to fall on her. She had read that Umer used to be taller than Mount Jaro, its neighbour. But the volcanic mountain had blown its top off. Perhaps a phantom of its earlier stature remained.

Maxine parked her Peugeot by the side of the highway. Near Umer, the grassland gave way to forest. She had found a clearing in the trees and simply driven off the road and into it. She hitched her backpack on to her shoulder and began the trek.

Jambo! Jambo! The children of the village at the foot of the mountain greeted her. They stopped playing and followed her for a bit. Her golden hair and pale skin were more interesting than their mock-hunting game. Maxine replied, Jambo! Habari? The children were surprised by her perfect diction in Swahili. They looked closely at this blonde woman. They saw her fragile beauty. They did not see the enormous strength within that lay dormant like the Umer volcano. They could not know that Maxine was more African than anything else. Her parents were British missionaries. They had settled near Ashura. And Maxine had been born. She loved this land and its people as fiercely as anyone of African descent. Perhaps more.

As she passed the market she exchanged smiles with a Maasai lady at the beer stall. The lady with her colourful wrapper and plethora of beads had probably walked twenty miles to come to this village market and the first thing she did was to buy a beer. She pried open the crown cap of the brown glass bottle of Furahiya Beer with her teeth. She threw her head back and poured the warm liquid down her throat. There could be no better advertisement for the drink than the look of contentment that spread on her face. Maxine was tempted to have a beer too but decided to have a swig from her water bottle instead. Hiking, high altitudes and alcohol do not mix well, as she well knew.

The path left human habitation behind and entered dense forest, some of the lushest in East Africa. The path then passed through an arch, a natural gateway to the Mount Umer trail. The arch was formed by two olive trees trapped permanently in the tight embrace of a ficus.

The trail got steeper. Maxine enjoyed the ease with which she could tackle the slope. But she came across a middle-aged German couple for whom it was a struggle. She greeted them and offered help. She selected an acacia tree that had a number of slender branches quite close to the ground. Using her Swiss Army knife, she fashioned six hiking poles from it. Four for the Germans and a pair for herself. She would not need hers until later but now was a good time to acquire them.

The couple’s gratitude was uplifting. It propelled her faster up the mountain. Soon, a dozen or so colobus monkeys joined her. They swung along on trailside branches, keeping pace with her. They chattered furiously at her. She chattered back. Maxine believed she could communicate with animals. She laughed out loud thinking that she could hardly be called an animal whisperer though – given the decibel level at which she spoke to these primates.

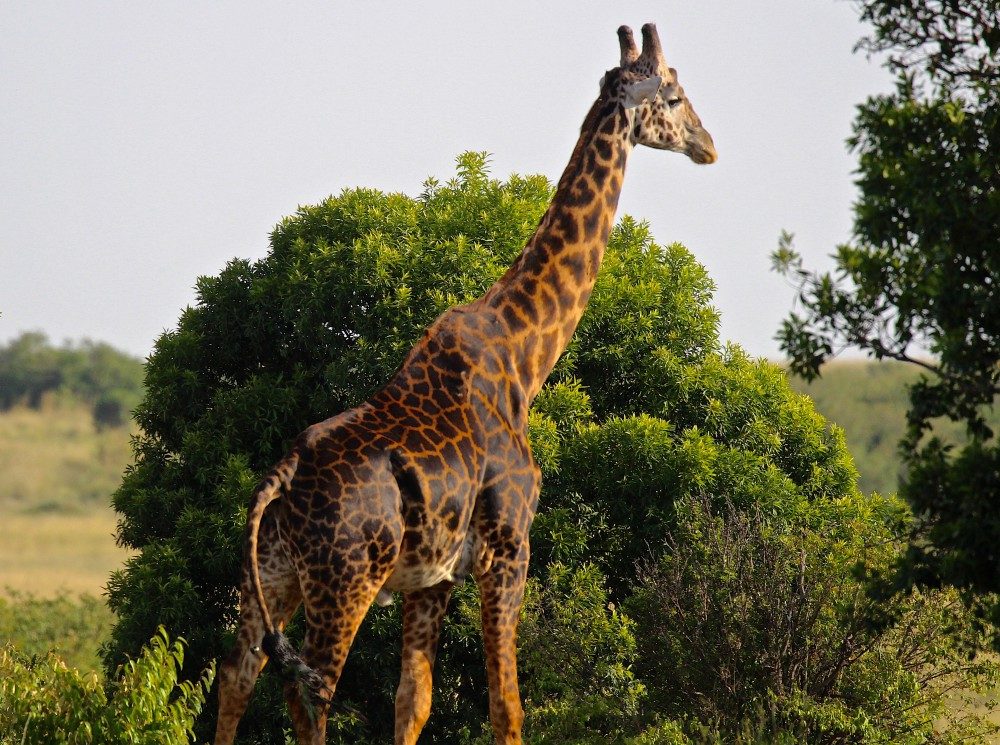

She came across a male giraffe. She was sure that he was the mate of the one she had met earlier on her drive. She looked up and told the giraffe that his partner was waiting for him downhill. The giraffe looked a bit startled and loped away in its characteristic gait that made Maxine think of slow-motion film.

It started to get colder as she gained altitude and the sun descended to the horizon. As the wind picked up, she imagined she heard singing in a soothing whispery male voice:

Malaika, nakupenda malaika

Angel, I love you, angel.

It was the voice of Julius Mkama. Oh, Jules, why are you not here beside me? Why Geneva? Did you have to study a complicated subject? Why couldn’t you specialize in something that was offered at the medical school in nearby Robinia?

Maxine remembered the freshman year college cultural programme where he sang this song. His voice had transfixed her. She had noticed him before, a tall and gentle young man. But that day the voice floated down from the stage and wrapped her in its embrace.

A relationship between a white girl and a black boy had been met with scepticism on campus. But, after a while, people realized that it was not the cliché bi-racial pairing that inevitably ended in disaster. Maxine had a trusting soul and Julius nurtured it in the nest of his quiet caring.

Malaika, nakupenda Malaika

Nami nifanyeje, kijana mwenzio

Angel, I love you, angel

But I, your young friend, what should I do?

He had applied for a scholarship from the Euro-African Education Fund. It was to study medicine in Switzerland, specializing in neural surgery, a subject that had become his obsession.

Maxine wondered when her giraffe, her Jules Giraffe, would come running to her. Perhaps he was already on his way. But the slow-motion gait made the journey long.

Towards dusk she was close to the tree line. The giant woods of the lower slopes had given way to a bewitched forest of gnarly lichen-covered dwarves. It was filled with the echoes of animal calls and the rush of a brook that flowed between and over rocks.

She reached Ngoma Cottage just before darkness. This simple three-roomed hut was known only to locals. It was equipped with a stove, fuel and food supplies of the kind that are not quick to perish. It ran on an honour system. People replenished stuff when they had supplies to spare. They used what they needed, when they did not. Maxine supplemented the delicious ham and cheese sandwiches she had carried with a packet of soup she found there. She prepared it on the stove with water from the brook. As she finished her supper, she was glad that no one else was using the hut tonight. She turned in, reliving the time she was here with him. She drifted off to sleep, enveloped in his warmth.

Maxine carefully picked her way along the ridge, her headlamp lighting the way. She had risen before three and set out. The rocky ridge of the crater offered a precarious hike. A false step and you could be at the bottom of the crater. She found it easier to navigate this route in the dark. The view of the ash cone was not there to distract you. And you were shielded from the vertigo-inducing immediacy of a possible fall. She shivered. But it was from the icy pre-dawn temperature, not fear.

Karuna Point. She reached it in time for sunrise. Sunrise: the word conjured different pictures for different people. For Maxine it was always this view. With the first rays, Mount Jaro slowly materialized in the distance as a massive yet ethereal iceberg. As the sun rose higher, this insubstantial vision solidified into the classically-featured mountain peak that it was by day, its expanse of white tinged with the flamingo pinkness of early sunlight.

Next, the ash cone of Umer came into view in the foreground. One did not know whether the wafts of grey around it were clouds or smoke escaping its still-active bowels. Finally, one could see the green floor of the crater, the cragginess of the ridge, the ash-strewn scree down its other side and the undulations of the many branches of the mountain stretching out in different directions.

Maxine poured a cup of tea from the thermos she had filled at the hut. She toasted the morning with it, its white wisps of steam paying tribute to the snows of Jaro and the smoky wraith encircling the ash cone of Umer.

The equatorial sunlight thawed the iciness of night and it was time to descend. Maxine started trudging down the ashen slope, her boots sinking into the powder. There were pebbles and rocks here and there but for the most part it was as if the scree had been passed through a sifter.

This is when the acacia-wood hiking poles came into their own. At first they helped her get a sure footing in the shifting ash. After a while, she gave in, as she always did, to the mountain’s wish: Her hiking poles became skiing poles and she let herself glide down the thick powder carpet of its slope. She giggled with the childlike exhilaration of it. Slide, slide, slide! She abandoned herself to the sensation of a semi-free-fall. She could not feel her body. All cares dissolved as she hurtled down towards the tree line. It was a giddy, giddy feeling. And all the time, Julius was with her. She just had to close her eyes to see the face, to hear the voice.

Kidege, hukuwaza kidege

Little bird, I think of you, little bird.

Maxine awoke. Her mother, Margaret Howard, was bustling about. Now, where is that remote? You fell asleep, she said. Let’s switch off the TV and get going. Maxine looked at the screen. A documentary on Mount Umer was coming to an end. Mrs. Howard found the remote. It must have slipped out of Maxine’s hand and fallen to the floor when she dozed off. Margaret pushed her daughter’s wheelchair towards the front door. She was saying, We’ll be late for the appointment. Let’s go! Dr. Agarwal doesn’t have all day to wait around for us, you know. Oh and do you have Julius’s letter with you? We mustn’t forget to tell the doctor his suggestions.

Julius would come back. His healing hands would embrace Maxine’s broken sparrow body. Life would flood back into her. She would get up and walk through the door, whole again. He had promised her the day it had happened, the fall. But the years stretched on since, as did the string of letters after Julius’s name. The string ended with ‘MD’ now. But Julius said he would come back home only after he added three more letters: ‘PhD’.

Maxine knew that Dr. Agarwal could do nothing for her. He was not up to date with the new developments. He was not skilled enough. He was not… Jules. But she went along for her parents’ sake. The weekly trips to the clinic made them feel useful. And hopeful.

When they reached the van, her father had already started the engine. The houseboy helped her mother push the wheelchair up the ramp into the back of the vehicle.

On the last trunk call, Julius had sounded excited. He had made a sudden breakthrough, something about cell transplants. She would stand again, he had said. She would regain sensation, he had insisted. She would walk to the altar, he had promised. Even through the telephone, the voice could soothe her with its certainty. Kidege, my little bird. My malaika, oh Max!

Please sing for me again, she had said softly.

Ningekuoa, Malaika

Nashindwa na mali sina, we

Ningekuoa, Malaika

Malaika, nakupenda Malaika

I would marry you, angel

I am defeated by the bride price, though

I would marry you, angel

Angel, I love you, angel

The baobabs rushed passed. She looked for green leaves. She thought she saw some. But she could not be certain. The van was going too fast. How can you feel so much, Maxine thought, when you can feel nothing?

[Cover photograph by Sumanto Chattopadhyay; Sumanto’s photograph by Sharmistha Dutta]

Comments are closed.