Snigdha Poonam’s book, ‘Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing Their World’, begins with a profile of Vinay Singhal, the founder of WittyFeed, a website famous for its curiosity-arousing, clickbait articles. I had no idea that WittyFeed – a website that seems to be aimed at a primarily western (read: American) audience – was founded at and is being run from Indore in Madhya Pradesh! Singhal, originally from “a small village in Haryana” and despite not having “encountered English before leaving their village” set up WittyFeed, “one of the world’s fastest growing content farms”, a website visited by millions, of which “80 per cent are foreigners and half [those] people are from the US”—all from “an all-glass office in a shopping mall in Indore”! This is what Poonam’s book is all about—stories of young people from north India – mainly Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand – who are not only dreaming seemingly impossible dreams but also, in some cases, turning those dreams into reality. The lead subjects in four out of seven chapters are based in Poonam’s hometown, Ranchi: the proprietor of a spoken English class, a stringer-turned-proprietor of a Pragya Kendra (a kiosk authorised by the government of Jharkhand to provide certain services to people on behalf of the government), a budding politician working with the BJP, and a winner of the Mr. Jharkhand pageant.

The only story about a woman is of Richa Singh, the first woman to become the president of the students’ union of Allahabad University who achieved this feat in two weeks! In the ultra-masculine political scene of Allahabad, men, “once they are done with college politics”, “join either full-time crime or the state assembly”. That is why, in the 127 years of Allahabad University, “[there] is a reason…why no woman had dared to stand for the president of the students’ union.” Singh started with reclaiming the space for women in the campus “where they came with their heads bowed and left…with their heads bowed”. As the president of the students’ union, she resisted violent attempts by the ABVP and stopped Yogi Adityanath, two years before he became the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, from entering the campus of Allahabad University.

What strikes immediately about these stories is the masculinity. Apart from a sense of responsibility that comes from being a man in India, there is the cockiness and that certain vulnerability associates with men. Poonam writes about her subjects: “Everyone I followed knew exactly what I was doing; not one of them was surprised at the fact of being chosen. Long before I showed up with a notebook and pen, they had known that someday someone would.” Vikas Thakur, who worked in the BJP’s IT cell in Ranchi, tries to impress Poonam with the several acts of rowdiness that he had performed – “maar-peet, gundagardi…contacts in the local police station” – to which Poonam wonders: “I didn’t always know how to react to these heroic stories young men told me about themselves.” The story on the cow protection army of Haryana is insightful in many ways. For one, I came to know that the members of the cow protection army were not dependent only on their job as protectors of cows—they also had day jobs. Sachin Ahuja, one of the gau rakshaks, sold insurance schemes from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., pumped iron from 7 p.m. to 8 p.m., and, 9 p.m. onwards, “he [responded] to the call of the cow mother.” Despite their claims of protecting Indian culture, one insecurity these men had was regarding women. Arjun Kumar, a 22-year-old man from Meerut and a member of the Bajrang Dal that kept young men and women from meeting one another on Valentine’s Day, “[was] not sure if he [would] find a job he’d like or find a girl who’d like him.” Ahuja, the gau rakshak, “[knew] better than to think he [had] any chances [with women].” In a show of emotions that is characteristically male, men like Santosh Thakur, the motivational speaker, and Pankaj Prasad, the stringer-turned-Pragya Kendra operator, despite earning enough money that enabled them to buy SUVs, still preserved their bicycles from their days as strugglers. For Prasad, “[the] point of the relic [the bicycle] was to remind his visitors of the distance he [had] travelled in his life”.

Some common factors binding most of the men Poonam interviewed were a dislike for the Congress Party and an admiration for Narendra Modi, and internet and social media. It was understood if the Hindu radicals sang paeans for Modi, but even Singhal “[saw] hope in…Modi…[the] tech-savvy strongman [had] everything a man like Singhal [wanted] in a leader.” Men like Singhal, Prasad, Thakur, and the workers at call centres in Delhi and other places built their careers on internet and technology. Poonam kept track of most of her subjects using their profiles on social media. Azhar Khan, the Mr. Jharkhand winner from Ranchi, runs away to Mumbai and finds support there from his several followers on Facebook.

Poonam’s writing is rich in observation and humour. She mentions the white towel which is a symbol of authority in a sarkari office in north India. Prasad, “[to] mark his elevated status [as an operator of a Pragya Kendra]…covered his revolving chair with a white towel”. Also, Poonam provides a closure to the stories of her subjects – especially those from Ranchi – by following up on them over months. Like, she tells Khan’s story from when he became Mr. Jharkhand in 2014 through when he planned to open an event company in Ranchi to when he is struggling “in the middle of a suburban slum in Mumbai” in 2016, and Singh’s story from being an independent candidate to contest the students’ union election to becoming a member of the Samajwadi Party. In Allahabad University, Poonam finds humour in “a middle-aged Brahmin [man] who rarely opened his mouth for fear of disturbing the position of the paan he was chewing.” Poonam finds humour even in the troubles she took to gather her stories. At Allahabad University, while covering Singh’s victory, she survived a bomb explosion. “Like everybody there, I [ran] for my life, except I [didn’t] know where to go. By the time I [found] Singh in the stampede, I [knew] I [was] done with Allahabad.” While doing the story on cyber fraud in call centres, Poonam went undercover as a job aspirant, “[interviewing] four times for a job” without knowing “what [she] would be selling if [she] ever got in.” Poonam entered the lives of her subjects as she spent time with them. Khan asked her to suggest a name for the event company he was planning to start, while an employee at a call centre asked her to pay monthly instalment on his car loan. Snippets like these make Poonam’s book a lively read, as interesting as the lives of the people whose stories it tells.

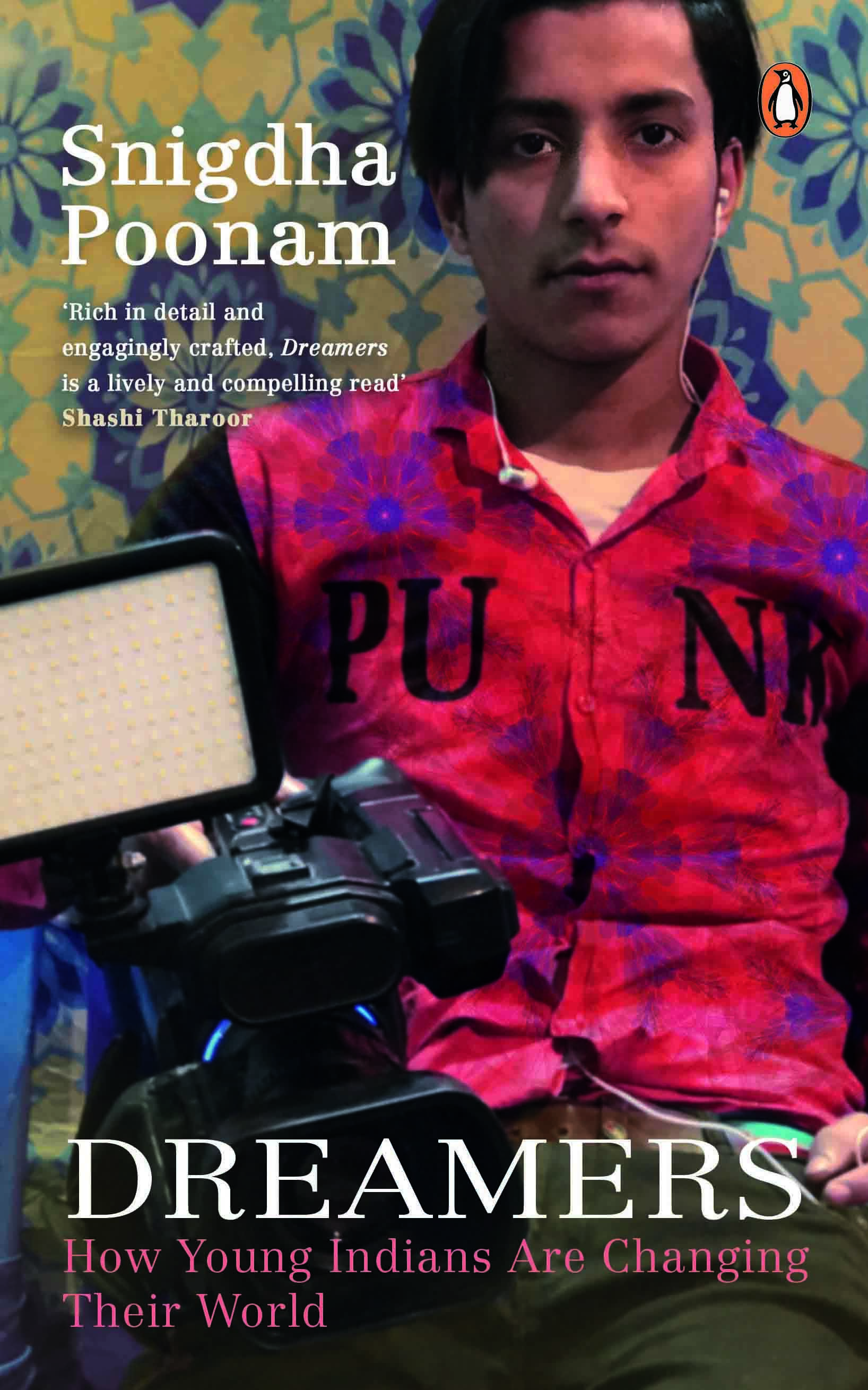

Title: Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing Their World

Author: Snigdha Poonam

Publisher: Viking (Penguin Books India)

Pages: 256; Price: INR 599