When Delhi BJP leader Nupur Sharma tweeted pictures of the 2002 Gujarat riots and attempted to pass them off as Bengal 2017, she was only being a loyal party soldier. In the BJP’s disinformation campaign, Bengal is now, to borrow a hashtag from one of the rabble-rousing channels, a ‘Hindu hate hub’. The graphic imagery of burning shops and vehicles and sword-wielding Islamists is only designed to further the communal divide and consolidate a potential Hindu vote bank.

It isn’t just Bengal. The Sangh Parivar’s propaganda blitz claims that the RSS is a ‘victim’ in Kerala too. While a return to power of the Left Front government in Kerala in 2016 has resulted in increased and condemnable violence against RSS workers in Kannur district in particular, the bloodletting has a long and gory history that dates back to the 1960s. Nor have the killings been one-sided: Official figures given by then Kerala home minister, Ramesh Chennithala, in 2015, suggest both the RSS and Left cadre have been victims.

That Bengal and Kerala feature so prominently in the BJP’s political narrative should come as no surprise. These are the only two large states left in the country (states with more than 10 Lok Sabha seats) where the BJP is still a marginal political party. A third state, Tamil Nadu, also has a limited BJP presence but in keeping with the state’s unique political ethos, the BJP is looking to ‘outsource’ its leadership to Rajinikanth, the reigning superstar of Tamil cinema. In two other relatively ‘weak’ states—Odisha and Andhra Pradesh—the BJP has artfully used local alliances, past and present, to expand its base.

Bengal and Kerala have certain similarities that make these states conducive for the lotus to bloom (the BJP doubled its vote share in both states in the 2016 assembly elections). Both states have large minority populations, ideal for the BJP to create a sense of ‘victimhood’ and position the party as a saviour of the majority community. In both states, the ruling parties have faced the charge of minority appeasement, making it even easier for the BJP to make inroads. In both states, the Congress is facing a steady erosion of its vote base while the rapid decline of the Left in Bengal has expanded the Opposition space considerably.

The nature of political Islam has changed in both states too. The syncretic Sufiist traditions in Bengal have been replaced by a more puritanical and radicalized version, with Wahhabist influences from across the border in Bangladesh now finding increasing resonance in parts of the state. A similar process has been witnessed in the Muslim-dominated districts of Kerala with money from West Asia being poured into local mosques and madrasas.

The rise of the BJP in these two states only exposes the failure of the self-styled secular class to offer a credible challenge to communal politics. A Mamata Banerjee, for example, may be Bengal’s unquestioned neta number one, but her political insecurities have made her vulnerable enough to pursue a rather short-sighted agenda where she has wooed the local imams and muezzins with the sole intent of cementing a large 27 per cent plus Muslim vote bank. In Kerala, too, the Congress and Left have competed to cultivate more extreme Muslim and Christian group leaderships to consolidate their hold over power.

That the politics of so-called appeasement has principally benefitted only a ‘creamy layer’ among the minorities reveals the hollowness of secular politics. In Bengal, for example, per capita incomes of the average Muslim remain well below the national average, statistics which suggest that acute problems of social and economic backwardness have scarcely been addressed. In Kerala, education has helped build a more egalitarian society but without necessarily creating more employable opportunities.

By building on local antagonisms, the BJP is playing with fire. Rather than provide a healing touch, the party seems keen to polarize communities further. Expecting the BJP to pull back from Hindutva is improbable; seeking a course correction from the ‘secular’ leadership remains a last hope.

Postscript: Nupur Sharma is not the first BJP leader to put out ‘mistaken’ riot pictures. During the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, BJP MLA Sangeet Som allegedly circulated images from Afghanistan’s conflict to incite violence. Far from being reprimanded, he is now a senior minister in the UP government.

[This July 2017 column is part of the journalist’s book about “tracking India in the Modi era”]

Author’s note: The BJP’s attempts to make a mark in Kerala have met with very little success. The party, however, is rapidly emerging as the principal challenger to Mamata’s dominance in Bengal in the future and hopes to make gains here in 2019. In the May 2018 panchayat elections, the Trinamool Congress won big but faced serious allegations of rigging, intimidation and violence.

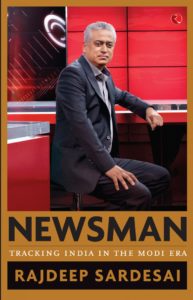

Excerpted with permission from Newsman: Tracking India In The Modi Era, Rajdeep Sardesai.

Rupa Publications; Pages: 256, Price: Rs 500

Comments are closed.